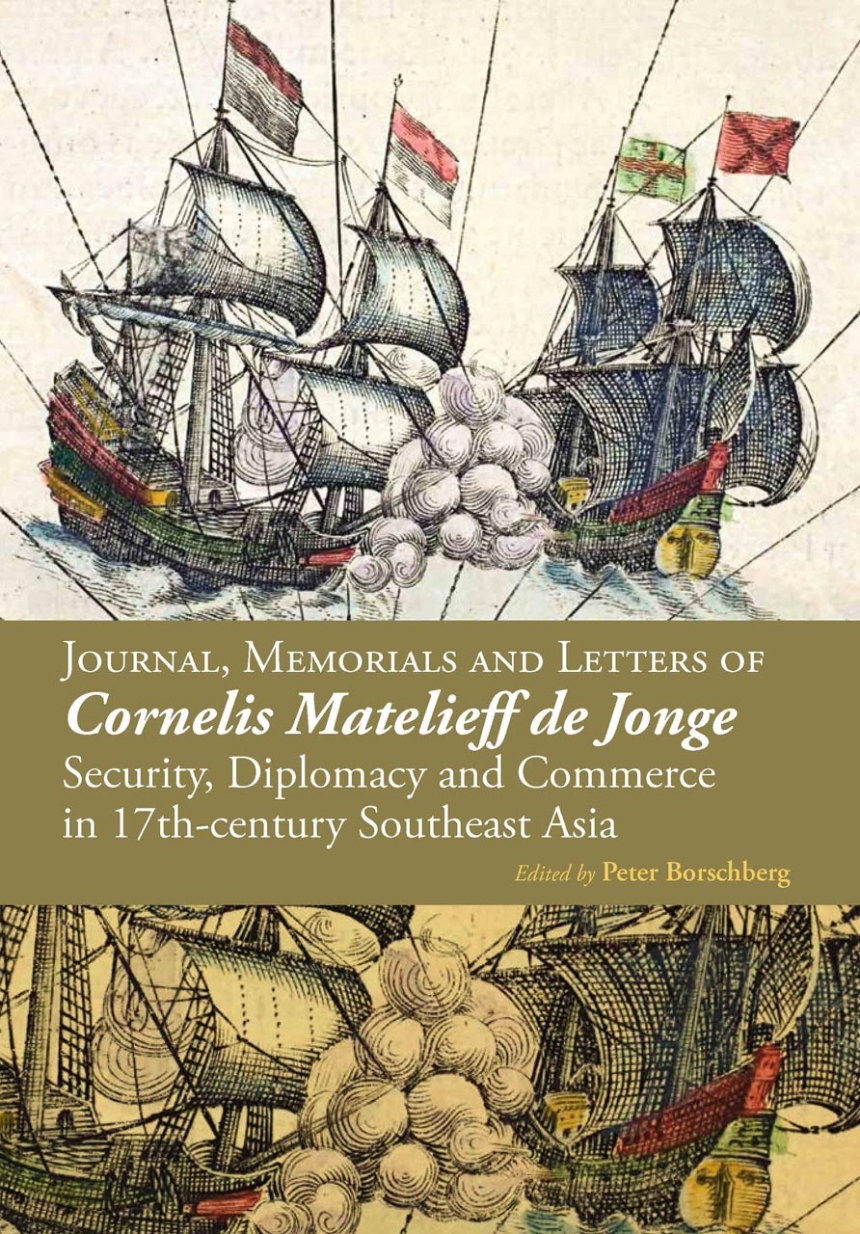

Journal, Memorials and Letters of Cornelis Matelieff de Jonge: Security, Diplomacy and Commerce in 17th-century Southeast Asia

Edited by Peter Borschberg

Publisher: NUS

ISBN: 9789971695279

Weight: 1505gsm

Pages: 704pp

Year: 2015

Price: RM174

Journal, Memorials and Letters of Cornelis Matelieff de Jonge: Security, Diplomacy and Commerce in 17th-Century Southeast Asia presents a collection of documents of vital importance in the early modern hiStory of European trade, warfare, and expansion in Southeast Asia. It features annotated translations relating to VOC Admiral Cornelis Matelieff de Jonge and his voyage to Asia (1605-08), their geographic focus is on present-day Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia, with additional references to India, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, China and The Philippines. Researchers specialising in early colonialism, international law, international relations, security studies, trade, diplomatic and company history will find that the texts offer a range of fresh and unfamiliar perspectives.

Cornelis Matelieff de Jonge served as a lifetime director of the Rotterdam Chamber of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). In 1605 he was appointed fleet commander of the company’s second voyage to Asia, and his mission was both commercial and military: he launched a major seaborne attack on Portuguese Melaka, arranged for the signing of treaties with the rulers of Johor, Aceh and Ternate, and founded the first Dutch fort on Ternate. His endeavours to open the Chinese market for the VOC, however, proved unsuccessful.

Following his return to the Dutch Republic in September 1608, Matelieff penned a series of epistolary memorials in which he identified problems faced by the company and suggested recommendations for their resolution. These texts were written at a formative moment in the company’s early history, when the directors were seeking to balance the pursuit of trade against the task of waging war with the Iberian powers east of the Cape of Good Hope. The directors aimed to meet the short-term expectations of the shareholders for a decent return on capital, but were also committed to investing heavily in expensive, long-term commercial and military infrastructure—an objective which consumed the profits, and more. With an eye cast on the unfolding of Dutch colonial power in Asia, the directors perceived the center of gravity shifting away from Melaka and the Straits region toward the area around the Sunda Strait and specifically the northwestern coast of Java. Matelieff’s letters and memorials mirror these dilemmas and trends. They showcase his business sense and military and diplomatic prowess, as well as convey his personal vision for securing the company’s long-term future.

It has been claimed that Matelieff was a man with an imperial agenda. Arguably, the proposals he spelt out in his writings acted as something of a blueprint for future action by the VOC—and indeed, the creation of the first Dutch empire in Asia. Based on what he had learnt about the way the Portuguese operated in Asia, he urged the directors to select a Strategic location that would be a permanent Asian base for the company’s operations. He weighed the merits of several locations—Aceh, Melaka, Johor, Palembang, Banten and Jayakerta. The last of these was his preferred choice, and was in fact taken by force by the VOC about a decade later-and renamed Batavia.

In tandem with the selection of a rendezvous, it was also Matelieff who proposed the appointment of a permanent supreme authority in the East Indies, a governor-general. The system that prevailed in the first decade of the 17th century, where each fleet commander exercised plenipotentiary power, clearly had limitations—Matelieff could not help but observe the propensity of fleet commanders to get in the way of each other.

Showing his business acumen, Matelieff held out the realistic prospect of monopolising the nutmeg, mace and clove supplies at source. He set the stage for creating the clove monopoly in 1607 by signing the VOC’s First exclusive delivery contract with the ruler of Temate. The company’s stranglehold over nutmeg and mace-producing Banda began in 1609. With regard to pepper, Matelieff advised against any attempt to control the market, and proposed an entirely different strategy. Since the supply of pepper was far too large to control, he advised the VOC to purchase pepper in large quantities and carry this spice as ballast on the return voyage to Europe. At home this pepper might be sold off at a price to recoup costs. But even selling at a loss would be worthwhile if it led to a glut of pepper that would erode profit margins and prospectively drive competitors out of business.

Reflecting debates that would plague the company for much of its corporate lifespan, Matelieff recognised that the VOC could not profitably trade everything. For this reason he suggested farming out parts of its monopoly to private citizen-traders. This proposal was clearly less palatable to the directors.

Apart from providing vita] insights into Dutch policy and strategy, the documents translated in this colleaion also furnish new and valuable information on the social and political structures of SoutheaSt Asian polities—including information about key leaders and their diplomatic maneuverings, their political agency. The documents allow the reader to eavesdrop on discussions between Matelieff and leading Malay personalities of the day, revealing clashes of priorities, expectations, and values. One example is the strikingly high value placed by Malay leaders on the preservation of life—which contrasted with the little value they attached to land or territorial ownership. The Dutch found such understandings difficult to grasp.

The birth of the Dutch Republic, its protracted war against Spain, and its shifting attitudes toward Portugal, are crucial for appreciating the backdrop against which the VOC and its relations with Asian polities would develop. This historical setting serves to contextualize the observations expounded by Matelieff—a perceptive analyst determined to seize business opportunities and grasp the political and economic structures of Asia. At a time of Europe’s rapidly growing engagement with this part of the world, Matelieff sought to assess the ways Europeans could and should deal with local rulers. In doing this, he helped to forge a primordial structure to VOC endeavours in Asia—a structure that, as it turned out, was to endure for the next two centuries.